Kendall is a 17-year old high school junior who runs track, is joining the high school debate team, and describes herself as good at “arguing her point.” She manages her active life with energy and enthusiasm until, rather suddenly, she started to have fever, body aches and back pain. Soon after, her urine started to smell bad. She was sent home from school with a fever and her mother took her to the pediatrician, who initially suspected a viral infection. When ibuprofen and rest failed to improve her fevers or aches and she was not able to eat well, her mother brought her to a local emergency department. There she was found to have a high fever and lower back pain.

The local physicians performed blood work and a urinalysis, which showed an abnormally high creatinine level (2.2 mg/dL) suggesting that Kendall’s kidneys were not functioning well. In addition, her serum white blood cell count was high (19.7 thou/uL) and her urine contained white blood cells (100/hpf) and bacteria, indicating generalized body infection that could be related to a urinary tract infection (UTI). Although the local physicians did not perform a urine culture, they administered an antibiotic and antipyretic, and transferred Kendall to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) for further care.

By the time Kendall arrived at CHOP, she was febrile, ill appearing and in mild distress. Her heart rate was elevated and she had tenderness in the right side of her belly. Her blood work confirmed acute kidney failure. Due to her symptoms, examination, and laboratory results the emergency room doctors were concerned that she had a condition known as urosepsis — an infection that spread from the urinary system to the body via the bloodstream.

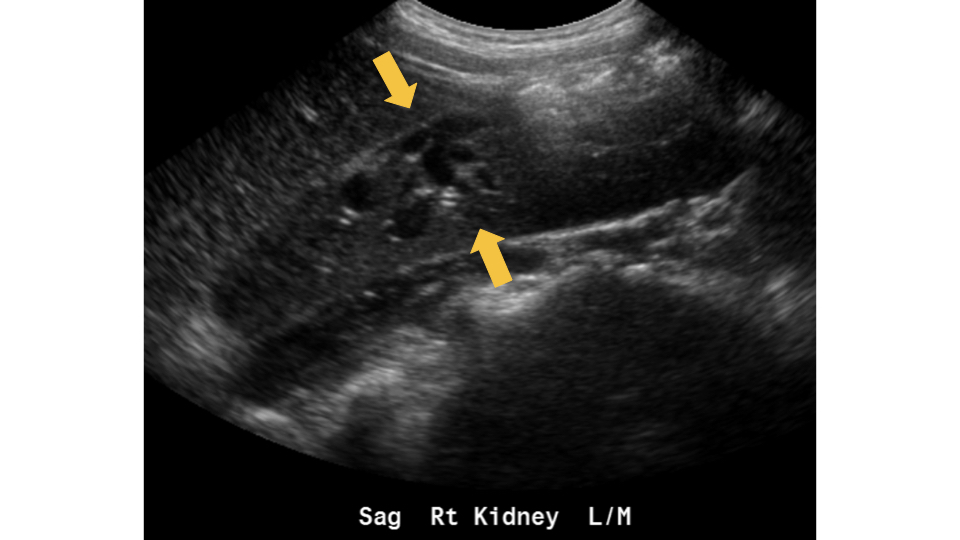

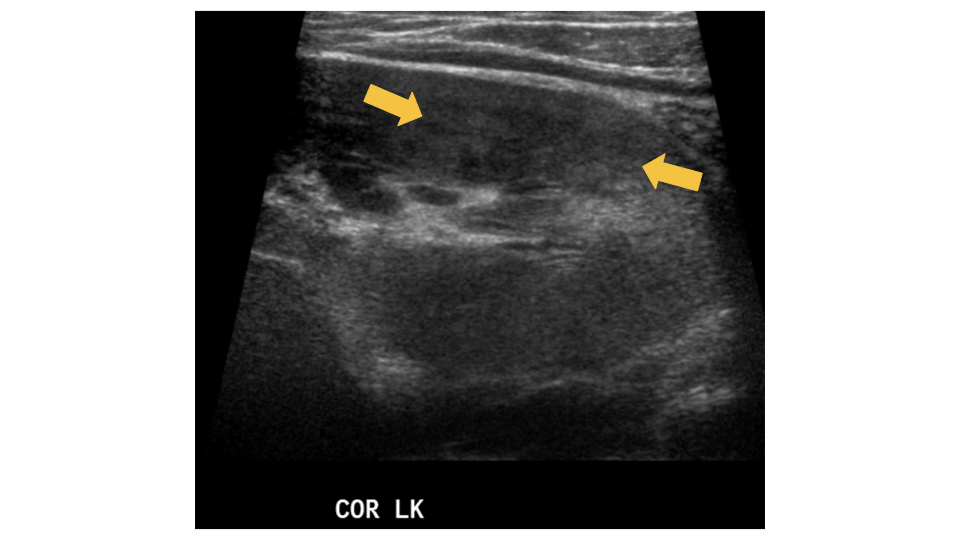

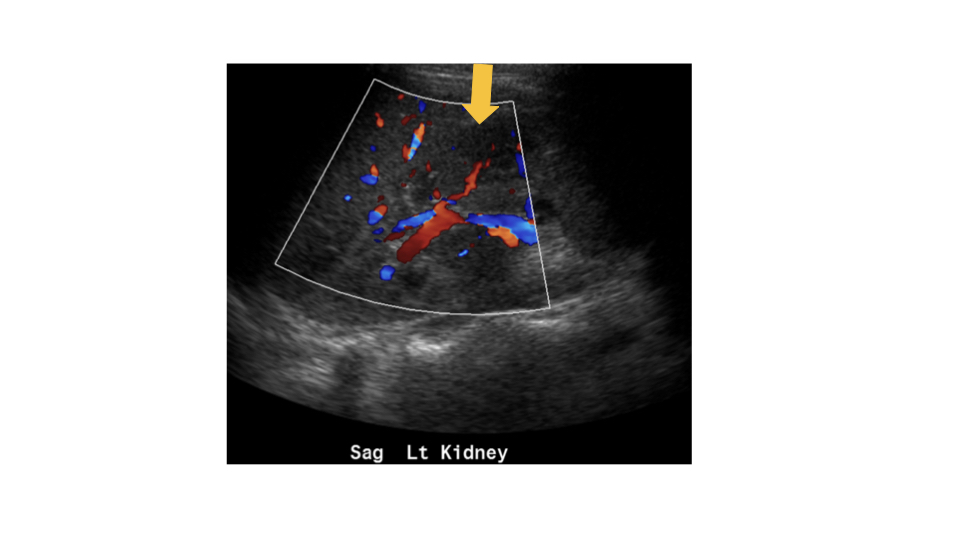

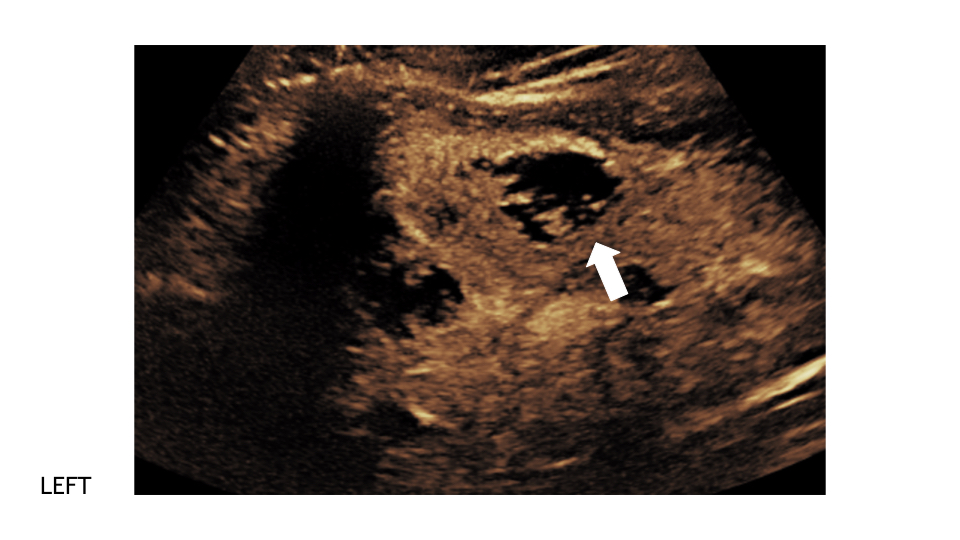

Kendall first had a conventional ultrasound exam of kidneys and bladder. Grayscale images showed a right complex cyst. Because of her symptoms, it was suspected to be an abscess, or infected fluid collection, likely from the bacteria that spread to the kidneys. There were areas in each kidney that appeared brighter or “echogenic” on ultrasound compared to normal regions of the kidneys. Given her current condition, these regions were most likely areas of kidney inflammation and infection compatible with pyelonephritis. Kendall was admitted to the hospital to receive intravenous antibiotics and close observation.

Further imaging was recommended by the urology and nephrology consultants to more clearly delineate the suspected abscess. But since Kendall had acute kidney failure, computed tomography (CT or CAT scan) with contrast was not an option. It is well established that the intravenous contrast (dye) contained in CT contrast agents can cause rare but serious problems in patients with poor kidney function.

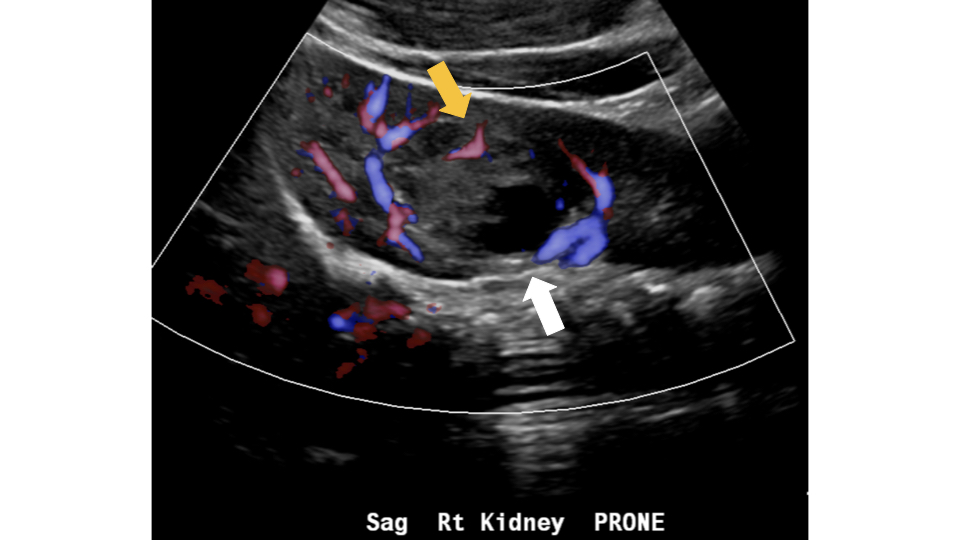

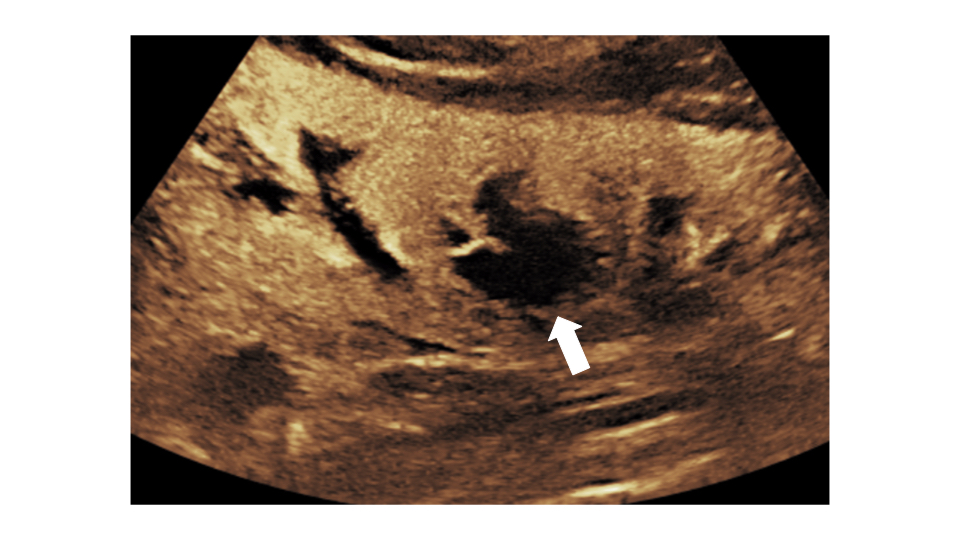

CHOP physicians then turned to contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) for further imaging. CEUS uses special contrast agents that are well tolerated by patients, including those with kidney disease. A CEUS scan can be performed at bedside or in other clinical settings using portable ultrasound equipment available at virtually every medical center in the USA, Europe and elsewhere.

Kendall’s CEUS scan showed an additional left kidney abscess that was not identified by conventional grayscale ultrasound alone. Given the extent of her infection, this new information helped physicians to determine she would benefit from having the abscess drained not only to culture the specific bacteria causing her infection to optimize her antibiotic therapy, but also to facilitate kidney healing.

She remained in the hospital for seven days. On her follow up appointment 2 weeks later, she was free from fever, back pain and urinary symptoms. Her kidney function returned to normal. Kendall and her mother were grateful that doctors could use the CEUS scan to pinpoint the cause of her acute medical crisis and administer the right treatment without putting her kidneys at further risk. She has fully healed and returned to an active and healthy life.

Susan Back, MD, is a pediatric radiologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.