Susan is a 42-year old mother of three with an extensive family and personal history of cancer. At the age of 26, Susan had been diagnosed with Stage III colorectal adenocarcinoma, leading to chemotherapy and surgical removal of the tumor and part of her colon. Since then, Susan has remained in complete remission and enjoyed good health and an active family with three young children under the age of 8.

When we met Susan, she was experiencing new symptoms of right upper quadrant fullness and discomfort. Concerned about recurrent colon cancer, Susan promptly visited her primary care physician, who referred her to our abdominal radiology department for further assessment.

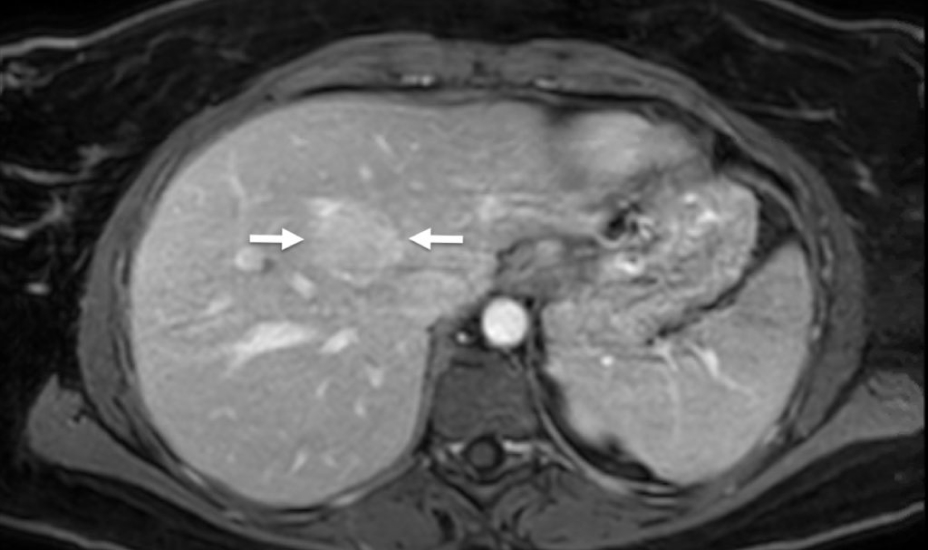

An initial ultrasound scan showed at least two liver nodules with blood flow on Doppler ultrasound. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the abdomen and pelvis, with a conventional gadolinium contrast agent, confirmed the finding of liver nodules. When her case was reviewed by a multidisciplinary tumor board, the liver lesions were believed to represent a common noncancerous condition called focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). However, these nodules were not seen on imaging done years earlier and her oncologists wanted to better characterize the findings using MR with a liver-specific MR contrast agent that also contained gadolinium, a metallic element.

Doctors explained to Susan that all MR contrast agents contain gadolinium, and liver-specific MR contrast agents represent a special type of MR contrast that is only retained by normal liver cells — thus distinguishing non-cancerous lesions, such as FNH, from malignant tumor cells.

After reading about gadolinium online, Susan told her oncologists that she was concerned about the risk of gadolinium deposits in the brain and the unknown long-term effects of gadolinium-based MR contrast agents. She also expressed concerned about her ability to metabolize gadolinium contrast. Susan refused the second contrast-enhanced MR and was scheduled for an ultrasound guided liver biopsy instead.

On the day of the procedure, we explained the risks and benefits of an ultrasound guided liver biopsy to Susan. Given the risks of the biopsy and moderate sedation, we again offered an MR with a liver-specific gadolinium-based contrast agent; however, Susan’s concerns remained and she refused any type of gadolinium contrast.

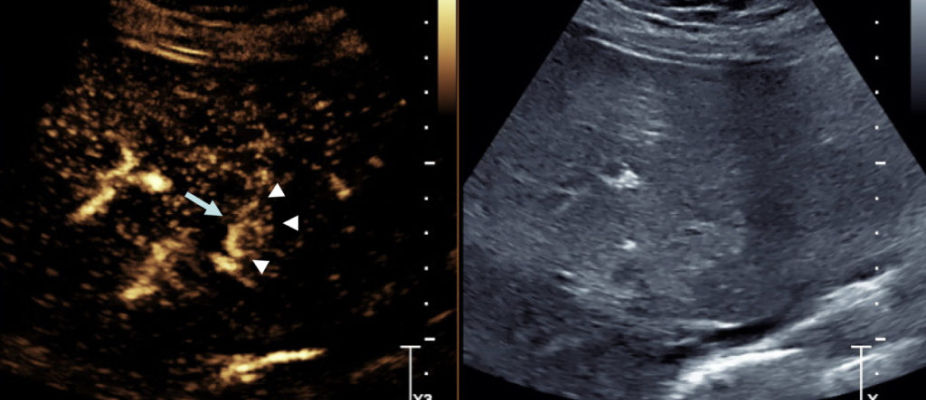

We then encouraged Susan to consider a contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) scan before undergoing the planned biopsy. We described how ultrasound contrast agents are completely different from gadolinium – rather than utilizing a metallic element that requires removal from the body through the liver and kidney, ultrasound contrast agents are comprised of tiny microbubbles of gas exhaled through normal breathing. These tiny bubbles appear bright on ultrasound, showing patterns of blood flow more specifically than with Doppler ultrasound alone. Susan agreed to the CEUS scan before her scheduled biopsy.

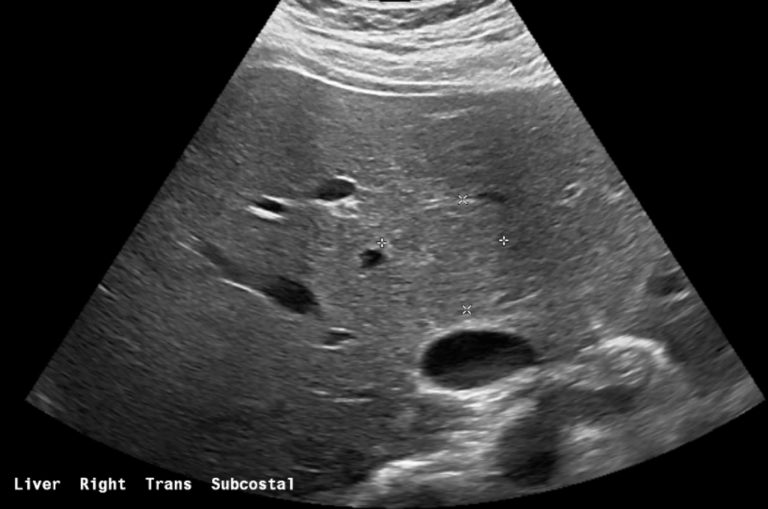

The initial conventional ultrasound images showed at least two vaguely discernible liver nodules (Figure 1).

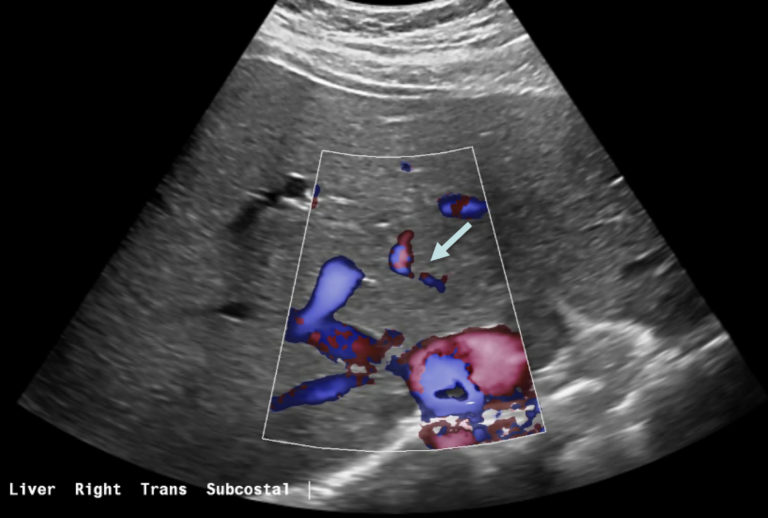

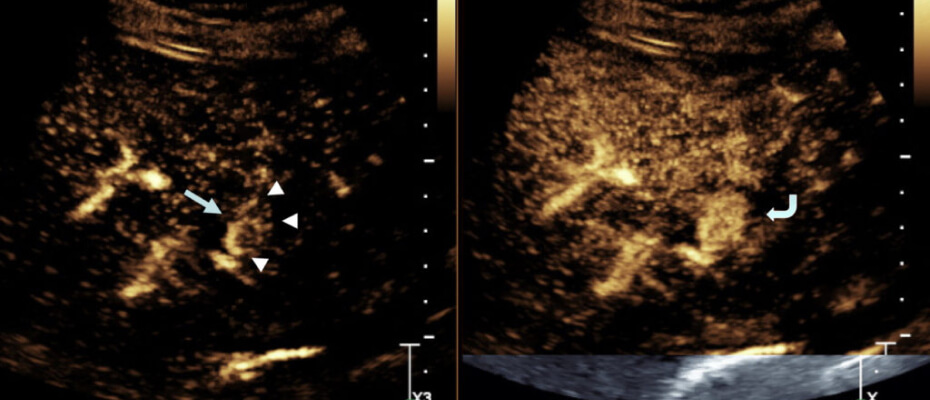

Color Doppler imaging showed both nodules had spoke-wheel like vascular structures centrally — a classic finding for benign FNH (Figure 2).

When the ultrasound contrast agent was injected, both nodules showed small arteries radiating from the center, called spoke wheel arteries, with strong enhancement compared to normal liver parenchyma (Figures 4 and 5). Given these findings and the pattern of contrast enhancement, which were unambiguous for benign FNH, no tissue sampling was considered necessary.

Susan was thoroughly relieved to have avoided a liver biopsy — and was even more relieved that her hepatic nodules were benign.

In this situation, CEUS proved to be a safe and effective imaging tool that allowed Susan to receive medical care the way she wanted — while providing the assurance she needed.